Unlocking the Depths: Technical Diving Drives Scientific Discovery

- Bill Nadeau

- Oct 9, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Oct 14, 2024

Technical diving allows scientists to access deeper underwater environments and stay longer at depth, enabling them to study marine ecosystems, collect samples, and conduct research in areas beyond the reach of conventional diving methods. Adopting these practices can be game changers for the scientific research community. The complexity associated with extended range diving does require a significant commitment to training - few in the scientific community are willing to make that effort.

Enter Dr. Malcolm Ramsay and Dr. Robert Dunbrack. Dr. Ramsay was an international authority on Polar Bears dedicated much of his work on the animals anatomy, specifically the efficiency of the bears digestive processes to re-synthesize protein from their own waste allowing the animal to fast for months when food was scarce. Malcolm had just started a new research initiative focusing on Six Gill Sharks, and was interested if there was some parallels between the animals foraging and feeding behaviours. During his Polar Bear research efforts in the remote Arctic Dr. Ramsay had learned to navigate the harsh northern conditions however, observing the elusive sharks was a whole new challenge as they are rarely found shallower than 130 feet (40 metres). Both researchers looked to technical diving to unlock the depths of cold ocean water and use those applications it would drive their scientific discovery

Despite the fact their Six Gill project is only in its early stages, many of the wrinkles associated with establishing a research methodology had been ironed out. One of them being able to follow these sharks deeper without the compromising effects of inert gas narcosis by using mixed gas technology. Somewhere between the Whale Shark and the Horn Shark in size but similar to both in behaviour, the Six Gill maintains a swimming routine that seemingly appears disinterested in the gawking divers who trail after it. Unless touched or harassed this gentle giant slowly cruises just inches off the sea floor while humans and marine animals interact in a complex relationship based on curiosity and fear. Even when provoked this cow shark only picks up its pace and swims just a little deeper and faster than a diver can keep up.

Like all sharks and other cartilaginous fish the Six Gill has no swim bladder so it tends to keep its forward momentum up to stop it from sinking to the bottom. Scientifically named Hexanchus griseus the Six Gill can reach lengths of up to 15 feet (and 1500lbs in weight) with some species reported as large as 25 feet in other parts of the world. Once thought to live only 25 to 30 years shark researchers are now estimating that larger sharks could be as old as 125 years taking decades to reach sexual maturity.

But very little is known about the Six Gill. Because they travel alone at extreme depths, depths that can be as deep as 6200 feet, not a lot of research has been done. In only a few remote locations around the world like Flora Islet off of Hornby Island on the west coast of British Columbia have these magnificent assembled shallow enough for human observation to take place in practical conditions. With no controlled fishery on Six Gills their numbers, if critically low could be endangered.

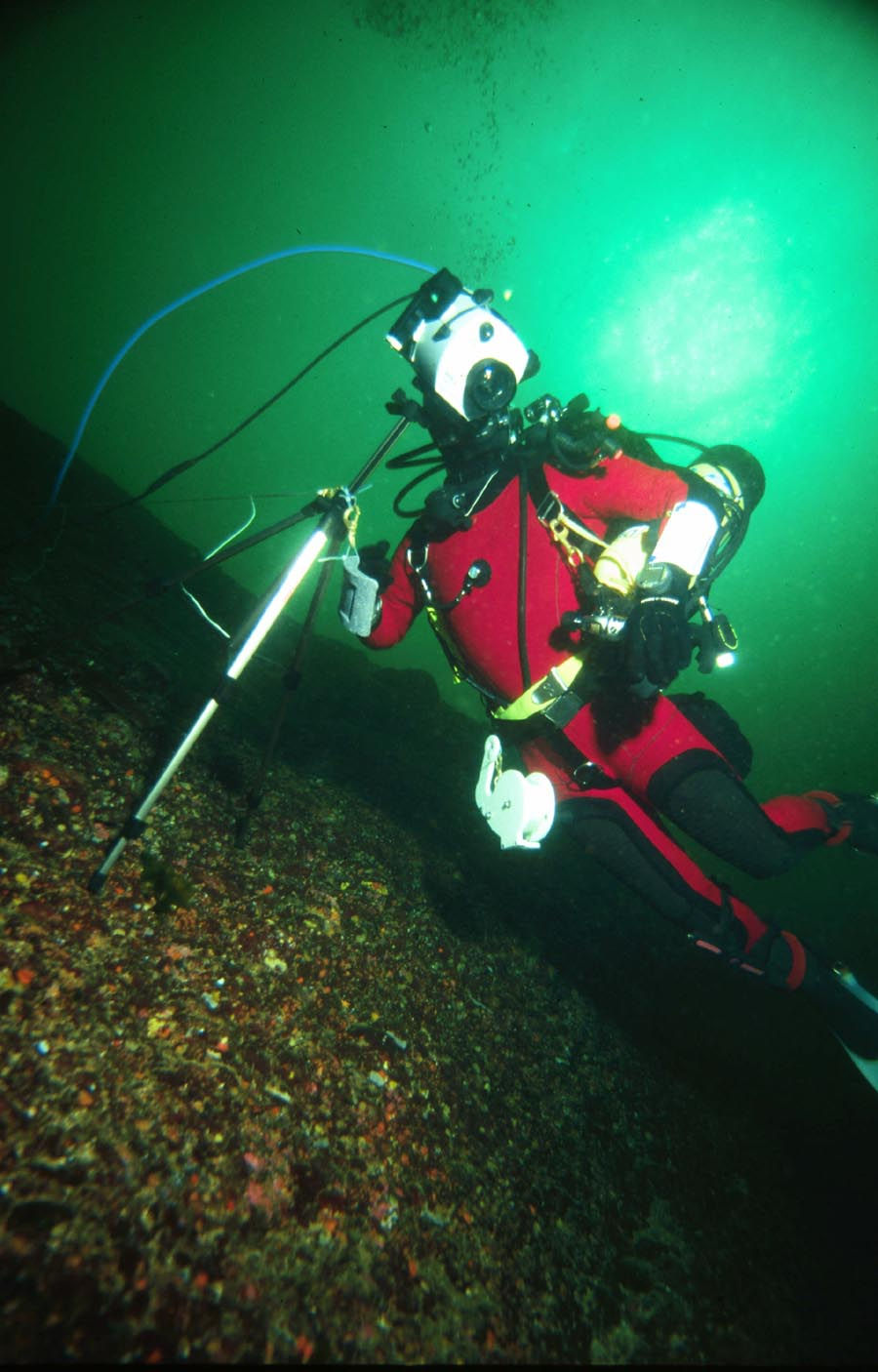

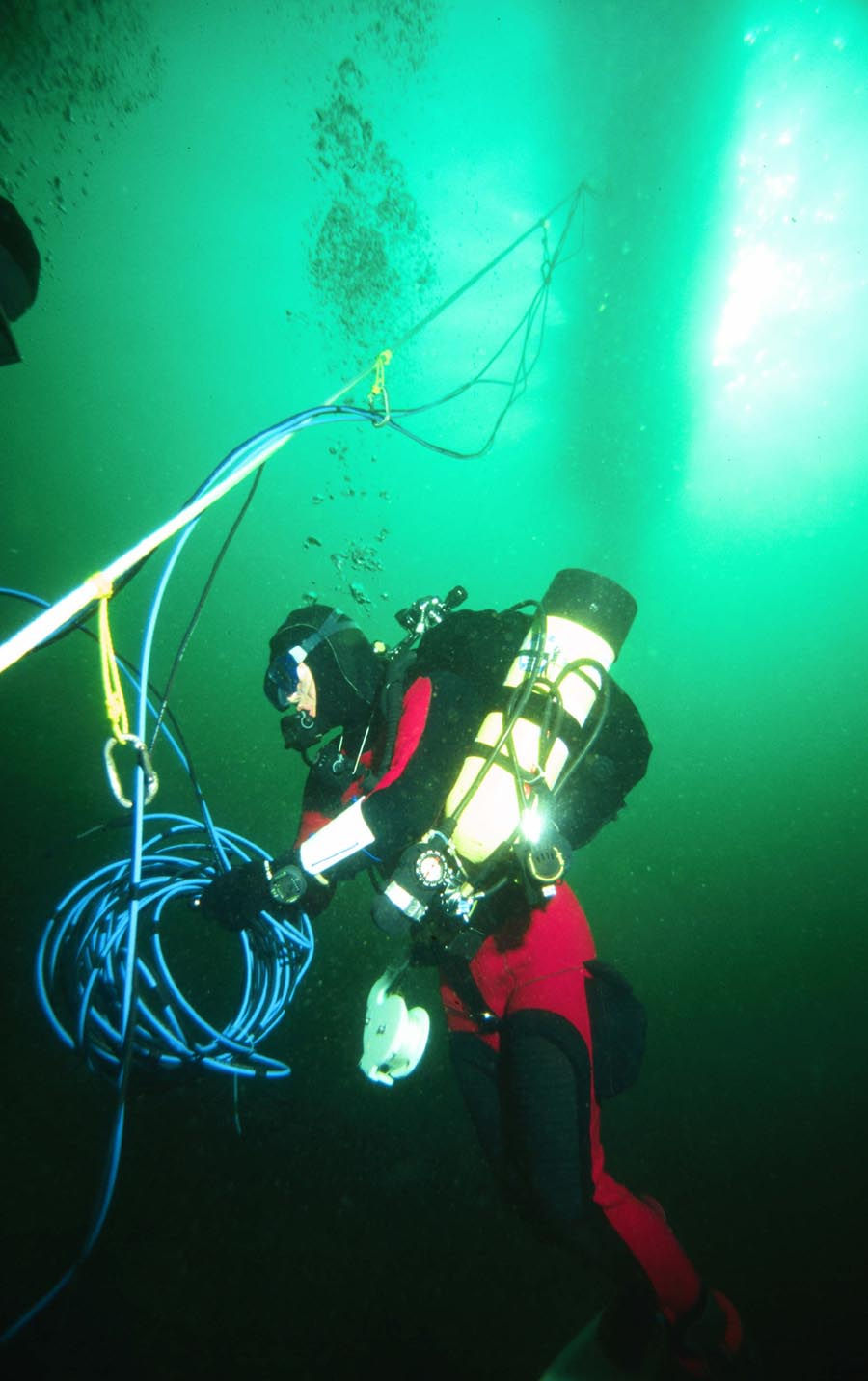

I first met Malcolm and Bob in 1997 when the two approached me to take a Rebreather course. The goal was to use closed circuit systems to extend bottom times, depths and observation capabilities while studying the sharks. Realizing that their shark research would take them in the 130-200fsw (39-60msw) range, mixed gas training also seemed logical. During two sunny weeks in September we completed their Trimix certifications while at the same time evaluating some more efficient ways to enhance their research techniques. For the scientists, diving to 200 feet (60 meters) with a clear head was a revelation in their potential for performing in advanced environments. For myself it was an honour to work side by side with two professionals who put me eye to eye with some of the biggest Six Gills I had ever seen. An extreme adrenaline rush would be putting mildly when you're at 170fsw and your wide-angle lens cannot fit the entire shark into the frame.

Dr. Malcolm Ramsay, a professor at the University of Saskatchewan and whose work had been featured in National Geographic, was part of an elite joint Canadian-US effort that took both country's Coast Guard Ice Breakers to the pole in an expedition that brought the world a little closer to the top of our planet. I asked Malcolm what parallels he could draw between the Six Gill and the Polar Bear. Expecting to hear a great analogy connecting the two animals biology and behaviour. I was surprised when he responded with an 'Oh, none really.' My thoughts became confused when I considered the similarities in the two animals size, singular nomadic behaviour and the fact that so little was known about both creatures but Malcolm persisted in remaining open-minded about his new project not ready to lay any speculation what-so-ever.

Dr. Bob Dunbrack, a marine biologist and professor at Memorial University in Newfoundland completed the well-rounded researching duo with a background on marine studies using a distinctive statistical/analytical approach. Bob adds a bead of consistency to their methodology. When the research vessel's compressor broke down, Bob's quiet nature turned into a confidence that was determined to make the universe right again. Within minutes he had disassembled the compressor casing and diagnosed the problem. How a person who works on the East Coast of Canada can commute across the country to where he and his family live in Nanaimo and still remain focused and relaxed is motivating to say the least.

Despite the team's unique and qualified vitae, they were still hampered by initial setbacks. Dealing with expensive and finely tuned electronic camera systems is challenging once Mother Nature gets involved. Between promiscuous seals knocking over the cameras and strong winds snapping expensive camera wires, dealing with the deep diving was a breeze. The objective of the project's first stage was to set up three high-resolution cameras at various depths feeding live continuous images to the research vessel above. Malcolm and Bob had hoped that over a 3-6 week period they could document enough Six Gill movement to determine the frequency of shark sightings and to try and determine what depths they more commonly frequent recording any identifiable marks each sighted shark had. This technique would also explore how and when they would extend their research without interfering with the sharks health or natural behaviour. With the assistance of Australian shark expert Kelvin Aitken, the research team explored possibilities of accumulating enough images to begin to identify single specimens much like Orca are tracked.

So little is known about these magnificent fish that Bob and Malcolm are reluctant to offer any early hypothesis. Every question I posed such as "Any ideas as to why they show up here and no where else up?" was met with a "None really - not enough data yet.". After spending the time with them I began to understand their responses. I have enjoyed diving with Six Gills at Hornby for years now and assumed like everyone else, that they only frequent this area for 2-3 weeks in the summer. During the ten days surrounding the Trimix program we observed over 20 sightings between the videos and the divers. On one dive with Rob and Amanda from Hornby Island Diving Resort, the divers missed an entire sighting. It began with a short descent to the camera to make some minor adjustments. Bob and Malcolm could see Rob and Amanda's group pass in font of the camera and then off the screen and along the wall. Fifteen minutes later and a large Six Gill passed in front of the camera. A short time after that the divers returned in front the cameras view while Bob and Malcolm watched live topside. When the divers surfaced they had reported not seeing any sharks or even aware of one in the area. How could a group with the sole intention of looking for Six Gills miss such a large animal? Very surprising considering Rob and Amanda's experience and knowledge of the area. On another occasion, Malcolm and Bob were diving and a large Six Gill nearly passed right over Malcolm's head unnoticed. Malcolm would not have known it if Bob had not caught his attention by frantically waving his light. During the return on the same dive it happened again only this time it was Bob who swam inches over another shark.

Are the sharks really only present in small numbers or are divers just not in a position of always locating them? I cannot help but compare it to planes that fly over head in the sky. We know that they go by all the time but unless we are outside, staring at the entire hemisphere from sun up to sundown, day after day, we may only be able to see a few. Diving for Six Gills offers even fewer opportunities for sightings than planes because of limited depth, visibility, light and our own observational ability (i.e.; visual narrowing due to the divers mask and possible narcosis). We also must consider that a dive really only lasts 30 minutes and dive teams tend to be looking in the same direction covering less ground. During the summer diving activity increases (especially around August) therefore it makes sense that there will be more sightings during this period. September is thought to be an off time for Six Gill sightings but out of six dives we spotted sharks on three. If the numbers were really as low as once thought then the odds of seeing sharks on 3 dives out of 6 is astounding. In fact over a 2-week period in September, 17 sharks were captured on 200 hours of video. That’s 17 separate sightings on a camera filming a small portion of the wall. Numbers suggest that we just are not looking in the right direction at the right time.

The following year we returned in June with Closed Circuit Rebreather systems. On three of four dives we sighted sharks and on two of those occasions there were as many as six different sharks in the area. The depths on these dives averaged between 150 and 180fsw.

Our sightings have been deeper (150fsw/45msw +) and perhaps the mixed gas medium helped reduce the narcotic potential of the nitrogen and CO2 retention increasing our observational skills but it has to make you wonder if we are drawing too many conclusions about these deep denizens. On the other hand, speculation without proof can be dangerous, one thing I have learned from Bob and Malcolm. Perhaps the shark numbers are in fact small and possibly may even be endangered. Only research will tell.

Now mixed gas trained Malcolm and Bob hope to return to the area each year and set up a number of self contained time lapse recording systems and expand the research area. As the research matures, patterns will evolve along with an improved methodology to study Six Gills. With hopes we have begun to see the beginning of the end of all the guessing, even if it takes going deeper for sharks.

In Memory

I was sad to learn about the loss of a great explorer, researcher, diver and friend —Dr. Malcolm Ramsay. Malcolm was killed in the spring of 2000 in a helicopter crash returning from the arctic. Malcolm was considered an international authority on Polar Bear research and has been featured in many publications including National Geographic.

A PhD graduate from the University of Alberta Malcolm spent a year as a Post-Doctoral Fellow with the Arctic Marine Mammal section of the Department of fisheries. When Dr. Ramsay was not studying polar bears in the arctic or Six Gill sharks on the west coast he was teaching biology at the University of Saskatchewan. An accomplished technical diver, photographer and academic his presence will be missed.

Comments